Fame Took Your Time — But The Film Still Deserves Depth…

Preparing for a historical role in a biopic or film should feel alive… until you realise it’s missing a heartbeat.

⚠️Actor, here’s the part no one warned you about:

The better you get, the less time you’re given to be that good.

You used to prepare like a detective—slow, deliberate, curious.

You had space to follow threads, chase details, get lost in libraries and footnotes.

Now you’re toggling between press tours and brand campaigns, reading scripts on planes, smiling through galas, nodding through interviews about a film you finished 13 months ago—while trying to prepare for the one that starts next week.

Tight schedules and looming deadlines cut into the prep time you used to protect.

The demands of multiple ongoing projects leave you with no choice but to rely on the fastest—and often least reliable—sources of information.

You don’t have the luxury of time anymore.

You don’t have the bandwidth it takes to dig.

Even if the velocity of your new life leaves almost no room to breathe,

you still owe the character the breathing room they require.

But the role still asks everything of you.

Fame took your time — but the new role still deserves depth.

That’s why your prep has to evolve.

You need sharper entry points.

Original sources that land fast, but hit deep.

So what do you do if you have no time to prepare?

You build likeness.

You construct gesture, posture, rhythm.

But it’s not a life. Not yet.

And even if the audience doesn’t notice—you do.

You feel the hollowness in the pause.

You feel how close you came.

You feel what it could have been.

This is for the actors who sense when something’s off—

who feel the gap between performance and resonance—

who know when a character hasn’t fully landed.

Before we go any further, you might be asking:

1. What is this essay?

It’s a reality check—

for actors who’ve been handed the wrong tools and told to make magic anyway.

It’s a reframing—

of what historical prep should actually feel like: handpicked and actually helpful.

It’s a doorway—

into a different kind of research, one that meets your instincts with real, historical material.

2. Who is this for?

For the actor who’s rising fast

—and running out of time to prepare the way they used to.

For the one caught between the glamour of success

—and the calendar that never leaves room to go deep.

For the one who wants more than surface-level prep,

—but doesn’t know where to turn.

The Unseen Cost Of Getting It Wrong

Let’s talk about what happens when the materials you’re given don’t translate into emotional weight.

You overcompensate.

You rely on trauma tropes.

You perform pain in a way that’s broad, not specific.

You work harder. You spend more hours alone. You search for more info, grasping for something—anything—that might let you drop into the moment more deeply.

Sometimes, it almost works.

But it never feels effortless.

You carry the prep like a weight instead of letting it anchor you.

And slowly, you begin to doubt your instincts.

You try to force connection.

You lose presence.

You burn out.

And the worst part?

You miss the one moment—the entry point—that could have made you fall in love with their world. Because yes, even in war, even in tragedy, there are things worth loving. That’s what helps build truth on screen.

But for now, you’re not building a life—you’re building likeness.

It shows. To critics. To survivors. To people who know.

And most heartbreakingly: it shows to you.

You know what it could have been.

Let’s see what could work better—for you. But first, let’s look at the three things that cost you the most time and energy while preparing for your next role.

Unseen Cost #1: Left to Figure It Out Alone

You, actor, have assistants who manage your calendar, stylists who make sure you look like the version of yourself the world expects to see. You have agents who negotiate your worth, dialect coaches who sculpt your voice, trainers to shape your body, and intimacy coordinators who help you navigate the most vulnerable scenes with safety and dignity.

Yet, when it comes to one of the most critical components—preparing for historical roles or biopics—you’re shockingly left to your own device.

Instead of receiving the same level of professional support, you end up scrambling through Google searches or relying on Wikipedia, often sifting through incomplete or inaccurate information.

This lack of reliable guidance can potentially lead to a cascade of problems: In the worst case? Misrepresentation of historical figures, distortion of key events, and the loss of authenticity that defines a great performance. The result? Bad reviews. A failed film. And ultimately, damage to your career.

So, despite everything, you’re determined to delve deep into researching this historical role. Here’s what you’re told:

- »The script is the Bible. Everything you need is in the script.«

- »There’s a memoir. It’ll give you insight.«

- »It’s a real person! Just start with Wikipedia.«

You try.

You highlight. You underline.

But somewhere around hour 4 of reading a meticulously footnoted book, you realise something’s off. You’re learning about events.

But not about fear. Or shame. Or helplessness. Or quiet joy. Or stubborn hope.

You end up with too much material that has already been filtered through the lens of a biographer.

You stare at the pile of books and the folder of PDFs—each one arguing with the next—and realise you have to sift through all of it yourself.

So you flip through timelines, hoping something sticks. Born in Hamburg, 1923. Married in 1944. Lost everything in 1945. But still—nothing feels real.

Because you don’t know what their kitchen smelled like.

You don’t know what they hoped for if they survived the winter.

Unseen Cost #2: »You Should Consult A Scholar. And Meet Eyewitnesses.«

So you talk to an expert.

Maybe you found them yourself. Maybe production made an appointment for you.

Maybe they’re brilliant.

Maybe they’ve published 14 books on this exact era.

And still—ninety minutes in—you’re left with fragments. Disconnected moments. Lists of random names and places. Nothing cohesive.

After almost 3 hours, your conversation with the expert ends.

As you leave, the professor wonders, »Why did they come so unprepared?«

You wonder, »Why couldn’t they see I’m new to this?«

Yes, you walk away with information.

But no resonance.

Three days later, a well-meant email arrives—with more PDFs.

Maybe even a voice memo from the professor trying to cram four decades of knowledge into ten minutes.

You’re expected to transform this mess into something real, visceral, moving. Instead, you get context without contour. Names without nuance. Accuracy without access.

And if you ask questions? The answers are full of caveats: »We can’t be sure.«

»Not enough sources exist,« and

»It depends on the region.«

OF COURSE IT DEPENDS. (History always does.)

But those answers won’t help you play the scene. Slowly, you begin to understand…Professors and academics aren’t taught to write for tension. They write analyses. They write to explain, not to embody.

- What a professor publishes isn’t made for actors. It’s made for students. For scholars. To impress other academics. It isn’t made to live in your body.

- Academics analyse history with the ending in mind—but your Air Force pilot had no clue that World War II would end in under three weeks.

- They follow the big arcs of history—not the small, human details that once carried unbearable weight for someone living through them.

But it’s not just the outcome-focused way academics approach the past that makes it difficult—it’s something else too.

- After researching a topic inside and out, often for decades, it becomes almost impossible for them to filter out what matters most. To condense years of knowledge into an hour isn’t just difficult—it feels almost unfair.

- And because they don’t speak the language of storytelling, professors often don’t realise what would actually be useful to you—the actor trying to embody a person from the past.

- Often, the language they use is dense, abstract, difficult to follow. This isn’t a criticism; I’ve spent years inside academia myself. It’s simply a bubble where people speak, write and publish in their own language.

Yet again, you’re buried in too much material—or in the wrong kind entirely. None of it suited for what you truly need.

Because your job isn’t to reconstruct historical facts. It’s to recover the heartbeat.

Then someone from production connects you with eyewitnesses.

You spend an entire afternoon with a few men over a 100 years old, and their octogenarian children, in a retirement home. Some of them can barely remember the names of their RAF pilot colleagues. One asks his much younger wife, »What date was I shot at again?« Another simply recites the »official« version—highly redacted, carefully whitewashed—and when you press with more questions, you’re left with nothing.

You start to sense—you ask yourself—whether you should have looked into original sources that were closer to 1944, not an old man’s blurred memory.

As you drive home, one thought keeps nagging at you: historical research is like a puzzle. You should have started with the edges—the clearest, most stable parts.

Piece by piece, the rest could have taken shape. But instead, production handed you just one fragment: the eyewitness meeting. And that was supposed to be the whole picture?

Then there are the family members of the protagonist.

Again, entire afternoons having tea with strangers.

If you’re truly honest, it gave you a glimpse—but filtered through a bitter daughter’s lens, or softened through a loyal nephew’s version. Later, in interviews, you can say: yes, you met the eyewitnesses, you honoured the families. It sounds important. But what you don’t say is: You spoke to the people who knew those who had lived it (but they weren’t them!). How little those secondhand stories actually gave you—and how much it cost you to find that out too late.

Again, you feel you should have gone straight to other sources: closer, more honest, less filtered.

It looked like support. It felt like prep. But it wasn’t what you needed.

So you end up doing emotional labour in a vacuum—trying to imagine fear. Trying to guess grief. You rely on archetypes. Gestures. Echoes of other roles.

And it shows. Not because you didn’t care—but because what you were given wasn’t made for what you were asked to do.

Unseen Cost #3: You Don’t Need the Whole Era—Just One Detail That Lands

Here’s one of the biggest lies you’ve been told:

That to truly understand the person you’re portraying, you have to understand their entire era.

So you start ordering tons of books. Watch endless documentaries. Read and reread timelines. You highlight your scripts and mark the margins with year after year after year. You feel the pressure mount.

And still—you don’t feel closer to them.

Because history doesn’t work like that.

You don’t need the whole decade.

You need the hour they stopped believing their father would come home.

You don’t need the entire war.

You need the moment they realised they weren’t going to make it to Christmas.

You don’t need their full biography.

You need the feeling of being 17 and holding your breath in a stairwell, praying the knock on the door isn’t for you.

The industry pushes you toward scale—»cover it all,« »understand the macro,« »honour the period.« But your job is micro. Your job is moment.

Your job is to take us so deeply into one hour, one moment, one feeling—that we believe the whole world exists around it.

If this sparked something—I break down how emotional entry points can help rebuild a life from the past, and introduce a different way to start your film prep—right here on the info page for my 1:1 intensive designed for actors on a tight timeline, called »Get To Know Your Protagonist«.

The truth is, the scene that stays with the audience isn’t the one with the perfect historical backdrop. It’s the one where you put your hand on a radio and wait. Where your mouth moves, but you’re too scared to speak. Where you hear a sound and your whole body tightens—not because the script says »fear,« but because you felt it.

One breath. one scene, one memory.

When prep is personal, even one detail can hold an entire era.

That depth cannot be invented.

It must be excavated.

Let’s sum it up, shall we?

Unseen Cost #1: You’re Left Alone to »Figure It Out«

You’re surrounded by experts for every part of your career—agents, coaches, stylists… But when it comes to preparing for a historical role, you’re sent into the past alone. Research support is treated like an afterthought. What should be a guided, focused process becomes a solo struggle through archives, articles, and endless conflicting advice.

Unseen Cost #2: You’re Handed Facts—But Not Feelings

You’re told to consult scholars, to meet eyewitnesses, to read endless PDFs. But what you’re given isn’t emotional access—it’s surface information. You’re left to imagine fear, guess grief, and build a performance from secondhand memories, timelines, and textbooks that were never written with actors in mind.

Unseen Cost #3: You’re Expected to Carry the Whole Era

You’re pushed to »understand the period,« to master the big arcs of history, to cover decades of context. But what you actually need is much smaller: One breath. One moment. One feeling that makes the whole world live inside your scene. One detail that unlocks everything.

Read on, actor: It’ll help you reclaim your prep time—not with more noise, but with the kind of clarity that lets you feel who this person was, and what it cost them to live.

What if it could be different?

Your work needs more than accuracy. It needs emotion. It needs entry points.

It needs someone to say:

Here. This is the last letter she wrote on European soil—just before she boarded the ship to New York City.

Here. This is the detailed packing list the German authorities sent them before being deported to a German concentration camp.

Here. This is the address he memorised, just in case he made it out.

These aren’t props. They’re portals.

They don’t belong in museums. They belong in your prep.

Because the minute you see them, read them, feel them—you stop performing. You start remembering.

And the audience can tell.

— They will feel that a ration card was never just a ration card.

It’s a moment where a man realises he will have to choose which child eats first.

— A scribbled floor plan isn’t just a map.

It’s a record of how to escape the concentration camp.

— A cancelled wedding announcement isn’t just heartbreak.

It’s fate folding in on someone’s entire future.

This is the difference between being prepared and being present. This is the difference between a scene that’s okay—and a scene that stays.

Because the right detail doesn’t inform you. It finds you.

It breaks your heart a little. And that’s the beginning of everything.

I’m not here to flatten the past… I’m here to help you feel its sharp edges.

And I think actors deserve something better than timelines and textbook facts to prepare for the most emotionally demanding roles of their careers.

They deserve access to history that breathes.

To emotional entry points, not just historical summaries.

To the kinds of materials that don’t just inform you—but change you.

Guten Tag👋I’m Dr. Barbara from Germany.

I’ve spent 15+ years working inside this world—as a researcher-for-hire. I studied history and archaeology, and I even wrote my dissertation on how to tell history in a gripping way.

So far, I’ve worked on over 130 film, TV, and literary projects as a historical consultant—helping creators avoid clichés, dig deeper, and truly feel the weight of the past. And I’ve published more than 20 books along the way.

But here’s what I realised: No matter how much you study, no matter how famous the person you’re portraying—you can’t improvise connection with the past.

That’s why I specifically work with actors who want to go deeper, but don’t have time to do the digging alone.

Let me find and hand you what helps you work—quietly, precisely, and with German thoroughness. So when you step into the scene, you’re not second-guessing, hesitating, or improvising: you already have what you need.

You already have a character in mind. You know who he or she is—but not how they felt.

Now you want to move past research overwhelm and into something that feels real.

Here’s what makes my work different:

I don’t just research for accuracy. I research for rupture. The kind that slips under the skin and stays there.

Just kidding—accuracy is a given. (I’m German, after all.)

Yes, I’ve been trained to decipher almost any handwritten script from 50 AD to 1950.

I have a photographic memory, and I rarely forget a name.

I’ve walked through concentration camps with eyewitnesses.

I found a prisoner-of-war no one else could trace. (It took me 27 minutes.)

I’ve followed forgotten trails through five languages, 11 archives, and one last box in the attic no one thought to search.

What sets this work apart isn’t just the depth—it’s that I can find what’s real, explain why it matters, and give you exactly what your character needs to feel human. That’s when we work together—1:1.

»Get To Know Your Protagonist« is a deeply focused intensive that delivers a custom 5–10 page file about your character. This can be delivered in under 2 weeks. The materials help you start building your character’s backstory. It’s built to answer the questions most sources skip:

- What was their greatest fear—and how did it shape everything?

- What did one ordinary day look like for them?

- What did their home smell like?

- What did they wear—did they allow themselves small, almost invisible deviations from what was expected?

- What did they never say out loud, because of the rules they lived with?

- What quiet forces—class, gender, religion, silence—shaped how they moved?

Emotional depth doesn’t come from guessing. It comes from historical evidence. Curated. Condensed. Made usable—for you.

If you’re tired of collecting facts that go nowhere, and want emotional cues you can actually use, this is where we begin a research collaboration. (We can always delve in deeper, and find out more later.) Let me give you what helps you work—quietly, precisely, and with depth.

So if you’re someone who wants more than gestures, more than guesswork—then this might be where your preparation for the next role really begins.

Let’s make the past real—on your schedule, for your role, in your rhythm.

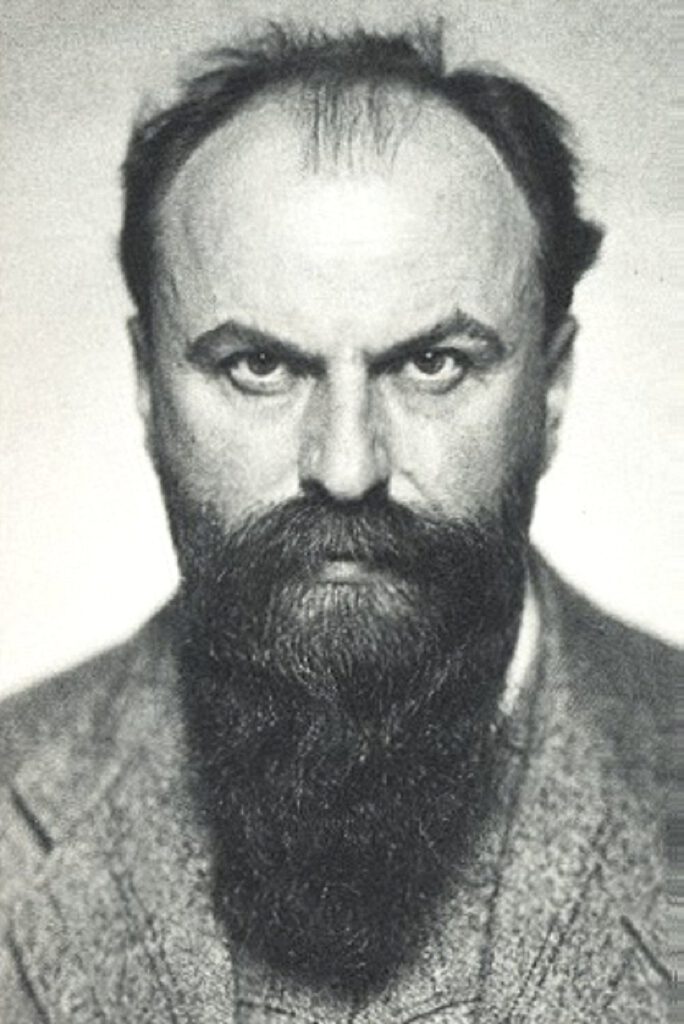

All images: CC0, photographer Nicola Perscheid // Judy Garland and colleag ues // Kathleen Ardelle 1921 // Syrie Wellcome via Wellcome Library London // Ziegfeld Girl in black.