The Actor’s Guide to Finding Authentic Sources On How People Spoke In The Past

// English Edition //

If you’re an actor and want to learn an accent for a role, the quickest way is to just listen to audios. So where do you find the best original, authentic sources on dialects from English-speaking countries?

Here is where I usually start my research.

Curated by historical consultant Dr. Barbara (more here)

Table of Content (click on the headline to jump to the section)

GB: Historical British English

GB: Your film is set in a city

GB: Your film is set in a specific region

GB: How ordinary people spoke between 1900–1920

GB: Search for famous people’s voices

US: Researching someone for a biopic?

US: Want to play a (famous) person from a big city?

CA: Historical Canadian English dialects

AUS: Historical Australian dialects

NZ: Historical New Zealand dialects

Imitating foreign accents in English

What to avoid when requesting digital recordings

GB: Historical British English

In a recent Variety interview, Cillian Murphy spoke wi

urces that actors can turn to.

Search SoundCloud for recent and historical audio recordings. The database can be used in a similar way to YouTube: search for ›Manchester dialect‹ or ›Birmingham accent‹ and you’ll find tons of audio clips. As many archives use SoundCloud to store and share digitised recordings, you might be lucky enough to find old recordings too. I found this 105-year-old song on SoundCloud, when an actor needed a voice sample. Give it a try. (But don’t get lost; set a timer!)

Search for these words for Soundcloud (and YouTube)

»Region or city + accent or dialect«

»Old voices + region or city + accent or dialect«

»Old recordings + region or city + accent or dialect«

»Region or city + accent or dialect in the past / in 1972 / in the 1970s etc«

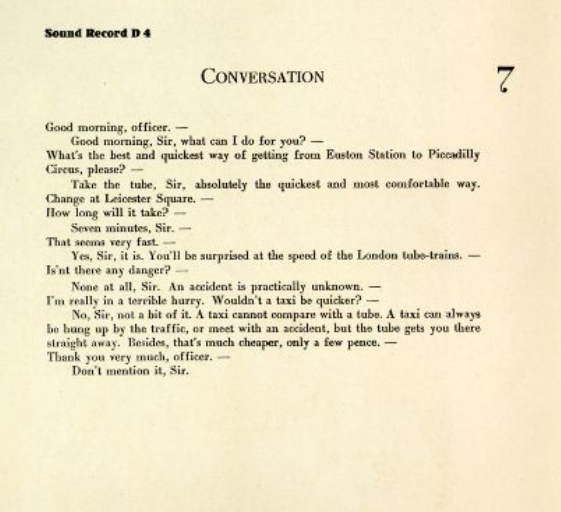

Is your film set after 1900? Then the British Pathé film database is the #1 resource you’ll want to start with. Past clients have loved to watch the news from the period they were writing about, or while they were portraying them as an actor. For example, if someone needed information about London between 1919 and 1925, they might search this on the British Pathé database:

»Famous person + the year / decade«

»Name of the person + the year / decade«

»Job of this person + the year / decade« for films on people with the same profession

»The region / city + the year«

If your character or subject has been in the news, you’ll find footage here.

If you want to search just the British Pathé channel on YouTube, be sure not to use the normal search bar at the top. Use the smaller search bar instead (see above ☝️), and you’ll just get results from this particular channel.

When searching, don’t mix up people with the same name. For example, »Oppenheimer« will give you 25 results. On closer inspection, it also shows people called »Franz Oppenheimer« and »Ernest Oppenheimer«, not only the infamous J. Robert Oppenheimer. Use the full name or quotation marks around the full name to avoid this.

A general note about the British Pathé films: They’re newsreels. These news clips give an »official« view of what happened. Some of my former clients like to watch them to see what people actually knew at the time. Why? We often look at the past with the benefit of hindsight, knowing how things will turn out. People didn’t know then.

You have to take your audience back to a state of uncertainty. You have to take yourself back to that uncertainty. Only then can you really play this person from the past. —

Even more films with (and without) sound can be found on the British Pathé website. Results can be filtered and sorted in chronological order which is helpful.

Need more sound recordings from Great Britain?

Enter: Sound British Library. The British Library in London has collected a wealth of sound recordings: Not only British songs but also speeches, interviews and other recordings from radio and television. The British Library audio recordings can be found here and here.

You can access these recordings on their website — but not all of them. A Reader Pass will give you access to even more digital sources when you research their online collections from home. A pass is (as far as I know) free and valid for a year. So next time you’re in London, pick up one at the British Library. You can apply for a Reader Pass online. If you visit the library in person, you will need to take a form of ID and proof of address to the Reader Registration Office to complete the process.

If you want to conduct research in the British Library in Euston Road, it’s a good idea to order any materials in advance so that you can start researching right away and don’t waste any time. However, their Earl Grey and the carrot cake in the cafeteria are delicious… (the cake has cream cheese frosting, and these little marzipan carrots on top. Ask me how I know… No, I have never had to wait 1.5 hours for materials I ordered, no, no, never).

Anyhow, their new project British Voice Bank has almost 8,000 recordings in it, spoken by speakers born between 1914 and 2006. With materials like this, they’ve created CDs in the past, such as Voices of the UK: Accents and Dialects of English (British Library Sound Archive) from 2010. The two CDs contains 170 dialect samples from all over the UK; they also come with helpful explanations in a leaflet.

What to put in the British Library catalogue search bar?

»The region / city + the year / decade« in quotation marks

The British Library even has a special section on accents and dialects. However — if this website 👈 does not open… please try again later. As the library has suffered a cyber attack, parts of their website are still down. The British Library expects search functionality to be back in place by the summer of 2024. In the meantime, they can help you by email at customer@bl.uk or bl_ref_services@bl.uk

GB: Your film is set in a city

If the film is set in a particular city, you’ll need to adapt the dialect of that place. Pay attention to socio-economic status and ethnicity, as accents or cadences can be very different from district to district — from rich to poor.

→ Example: Birmingham has a City Sound Archive run by the local museum. While there are no sound recordings of the original Peaky Blinders, this database and another sound archive preserve Birmingham recordings from the 1960s–1990s. (Bonus: If you want to throw in the occasional authentic expression, here’s a handy list of words from around town.)

→ Example: Manchester recordings. You can browse their archive catalogue with over 35,000 sounds here.

What to put in the search engine?

»City Sound Archive + city name + (maybe country)«

»Digitised + name of the city + (maybe country)«

»Digitised + lives in the past + name of the city + (maybe country)«

»Old recordings + name of the city + (maybe country)«

»Film and sound archive + name of the city + (maybe country)«

Why the country? If there’s also a Birmingham in the USA, this may influence your search results. Be specific when searching and always double-check what you find.

GB: Your film is set in a specific region

The same search method also works for a county or district. Type »sound archive + name of the county« into an online search engine. Even small institutions or initiatives in rural areas have started collecting local sounds, lectures, speeches or interviews with eyewitnesses. Sometimes these are digitised and available on their websites. Sometimes you have to travel there and listen to old CDs, LPs and cassettes.

→ Example: Recordings from Wessex

→ Example: Recordings from Orkney

→ Example: Recordings from Dorset

GB: How ordinary people spoke between 1900–1920

My favourite source for British dialect comes not from Britain, but from Germany. During and after the First World War, German linguist Wilhelm Doegen, travelled to many Prisoner Of War camps in Germany. He wanted to take advantage of the fact that people from different countries could be recorded, all in one place. He had previously developed a better method of recording on wax cylinders (which was brand new at the time).

Between 1910–1914, British authorities had actually commissioned Doegen to travel all over Britain. His task? To record normal, typical conversations between local men and women. So, the German expert recorded anything: from conversations about the tube (is it safe? Is a cab safer?) up to choosing the perfect hat or just about the weather.

If 1900–1920 is the era you need to research, and you’re in need of a special British dialect from the past, this is your resource.

Here’s how to access this knowledge. First, browse the different dialects here: Overview of English variants // Welsh // Gaelic—Scottish

Did you find a recording that has sparked your interest? Then you need to reach out. The Sound Archive in Berlin is in the process of digitising these wax cylinders and digitally enhancing the old recordings, some of which are over 100 years old! A selection of what they collect is already available on CD and can be purchased. — Inquire whether the recording you are looking for has already been digitised. You can email them in English. Their website states: »Please bear in mind that processing your inquiries can take up to two (!) weeks.« So contact them well in advance by email at lautarchiv@hu-berlin.de. You can only visit the Lautarchiv Berlin by appointment. — Here are two sample pages from Doegen’s recordings in England.

If you’ve read this far, then you‘re serious about your craft. Do you need to prepare for your next role, but you are pressed for time? I am a historian who helps actors understand their time and setting. In case we haven’t met: Hi, I’m Dr Barbara and I too research with German thoroughness. This is my mega-resource for English sound recordings that can help an actor prepare for a new film. If you need even more background information on your character or setting, and you want to save some time, contact me here.

GB: Search for famous people’s voices

Three options. Yes, start your search on YouTube. Then move on to smaller, lesser-known video portals. Try Vimeo first. Then move on to Google search, type in the name of the famous person and narrow down your search by clicking »videos only« 👇. Continue to search for TV documentaries about your person, your subject and their era (try different keywords). Those will also contain speeches of and interviews with this famous person.

What to search on Google?

»YouTube + voice recording + name of the famous person«

»YouTube + speech + name of the famous person«

»YouTube + documentary + name of the famous person«

»Vimeo + voice recording + name of the famous person«

»Vimeo + documentary + name of the famous person«

»TV documentations + name of the famous person«

»Documentary Hub«

»Documentary Hub Alternatives«

Search the media library of a TV or radio channel

Let’s stick with a UK example, but this could be adapted for any country. Often, radio and TV stations are the brains behind entire web portals on historical topics, such as these portals on the Berlin wall, wars of the 20th century or London in the Blitz during the Second World War.

As they have tons of audio material to use, they may have created radio features or films about the person you want to portray. Due to copyright issues, these features don’t usually end up on YouTube. But you can find them in the channels’ media libraries.

What to search on Google?

»Mediathek + name of the famous person«

»TV media library + name of the famous person«

»Name of the TV or radio station + mediathek + name of the famous person«

»BBC iPlayer + name of the famous person«

»Radio archive + name of the famous person«

»Radiothek + name of the famous person«

This! ✨ »TV / radio + From the Archives + name of the famous person«

Search for CDs with voice recordings

I can hear you protesting already, generation Spotify, but bear with me… Often, old voice recordings can’t be put on Spotify because of copyright issues. They can’t be played in podcasts because of copyright issues. But back in the 1990s, some archive or radio station might have pressed the voice of that famous person you’re so desperately researching on a CD. Try searching Amazon and other online stores for those CDs.

For my research clients, I’ve unearthed the only audio recording of legendary British writer Virginia Woolf on CD (ok, I admit I found it a few years later on YouTube, too, but that’s not the point. Search words for YT: »Virginia Woolf voice«). I also found the original recording of the daughter of women’s suffrage movement leader Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel, and original recordings of the Nuremberg Trials — all on CDs. Search in online book stores, but also in online second-hand book stores. And don’t forget Ebay.

Which search terms should be used?

»CD + voice recording + name of the famous person«

»CD + speech + name of the famous person«

»CD + name of the famous person«

GB: Scottish Sound Archives

A number of Scottish institutions have been collecting and archiving sounds for some time now. For actors wishing to learn a particular variant of the Scottish language, this means that there are several good places to start. Archivists and scholars will be happy to help you find a particular dialect.

The first source to start with is a Scotland-wide archive project. Browse the Scotland Sounds here and here.

Even more recordings can be accessed at the Digital Archive of Scottish Gaelic (also, their Soundcloud contains many interesting audio samples).

And finally, check out the Sound Archive at the Edinburgh University (mail inquiries: HeritageCollections@ed.ac.uk). Browse their catalogue here.

Ireland

Again, Wilhelm Doegen’s early recordings captured the voices and songs of ordinary people. He and his assistant travelled all over Ireland between 1928 and 1931. Their recordings have now been annotated, enhanced and digitised. You can listen to them on this website: https://doegen.ie

If you remember the YouTube comment at the beginning: Yes, YouTube brings you recordings from your area and time… but you’ll never know if the person speaking was brought up rich or poor. —

Not so here. Professor Doegen has annotated EVERY. SINGLE. RECORDING. He made notes about the person themselves, what their social status was, how long they had been in school, what their father’s job was, whether they had moved, whether they had been abroad, etc. etc. He wrote everything down with German thoroughness. Meticulously.

You can now browse by county, speaker or title using the links on the left of their website, or by clicking on a county on the map. You can also browse for information about the speakers’ backgrounds. Start your search here: The Doegen Records Web Project. Irish Dialect Sound Recordings 1928–31.

So, if you want to replicate an Irish accent or dialect from the 1920s or 1930s, and you want to be extra sure it’s correct according to social status, then this is your resource.

And this one’s for Cillian Murphy; it’s from Ireland. Thank you for giving me the idea to write this resource. Here’s a song that was sung by an Irishman over 100 years ago, and we still have the joy of listening to it today.

The USA

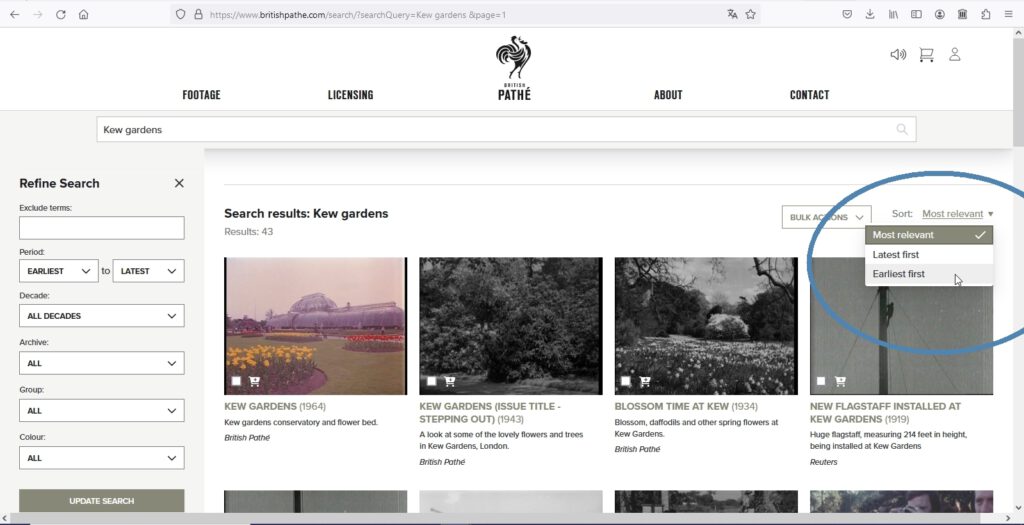

Let’s cross the pond to the United States of America. We’ll start with the most promising database for old recordings, at the Library Of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/audio/ To find these audios, narrow your search in the left column. Choose »audio recording« (otherwise you will also get research results mixed with books, noted music, films, photos and drawings). Be careful not to mix up »date recorded« and »date digitised«!

Also don’t skip the digital collections that the librarians have curated. Is there one from the decade you want to research? Let’s have a look: https://www.loc.gov/audio/collections/ These collections may contain audio that the person you’re portraying would have listened to at the time. For example, would he or she have listened to this original speech by Amelia Earhardt?

You can sort the items so that the oldest are at the top of your list.

USA: The American Memory Collection

What a chaotic mess and a pain to search: This database probably hasn’t been updated since 1999. However, from time to time I find great sound bites here. For example, what ordinary people were saying on the street the day after the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941. Or what former slaves said about slavery in the 1930s. It’s priceless to have these direct, unfiltered reactions. — Access it here. However, the only way to avoid getting lost in this database is to work with a timer. I set a countdown to 30 or 60 minutes and then just stop.

USA: Researching someone for a biopic?

Try to find out if this person’s personal photographs and papers have been given to an archive or library.

What to put in the search bar?

»Name of the person + digitised«

»Name of the person + collection + archive«

»Name of the person + estate«

An example: Leonard Bernstein

The Library of Congress in the US stores many collections; one of them is a special collection of Leonard Bernstein’s recordings and documents. You can browse the digital collection here and here. Myriads of unpublished photographs can also be found. And there’s even an option to select just »audios«, which leads to original »voice recordings« of Bernstein…! So when Bradley Cooper was prepping for his role in the film MAESTRO, he could have listened to these mostly unpublished conversations, speeches and interviews of Leonard Bernstein.

Why search collections? Compared to what you find on YouTube, you’ll often find unknown recordings from conversations in smaller, more intimate settings — not big speeches in giant venues. As an actor, you’ll get a little closer to how the person would have sounded like in private conversations.

USA: Want to play a (famous) person from a big city?

Before you do anything else, check in with the libraries and archives of this particular city. They will probably have a collection on that person. If not, they may be able to provide material on similar people from the same era.

What to put in the search bar?

»Name of the person + city + library«

»Name of the person + city + archive«

For example, the New York Public Library collects sound recordings related to the history of New York; access them here. »The Archive accepts reference questions by e-mail«, the website says. Include your full name and mailing address. Their email address is rha@nypl.org. Here is the search bar: https://archives.nypl.org

If you’re interested in Early US speech, wording and phrases, then this book is for you: The Early Days of American English.

Sign up for The Waitlist, and get an email when I write another mega resource like this one.

You’ll also occasionally hear from me whenever I have free slots for consulting sessions on character development and historical setting research.

Historical Canadian English dialects

Montreal SpokenWeb is a meta collection and lists more than 70 Canadian sound archives, some of which have recordings of native people. Search their database of over 700 recordings here. (Since they’re moving the catalogue to another website, there may be some glitches.)

Other digital collections from Canada can be accessed here, here and here.

The Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling collects and researches voice recordings from a variety of social backgrounds, including Haitian street gangs in Canada and factory workers. If you’re looking for a very special accent from Canada, they may be able to help: https://storytelling.concordia.ca/

Historical Australian dialects

You can find great examples in this Australian Ancestors database. For each person, they give their exact age and location (e.g. born 1895, now 78 years old + their hometown) which can help you find the right city soon. They also give explanations how to replicate these accents, for example: »The speaker uses an older form of the ›l‹ sound in bull, alone, along and ankles.« Contains many interesting bits.

What major database do we have for Australia? The National Film And Sound Archive (NFSA) collects the Australian sounds of the year, as well as historical recordings. Listen to digitised songs and speeches from as early as 1897. Other early recordings include Tasmanian Aboriginal women’s songs from 1899, and wax cylinder recordings of the Arrernte, Anmatyerr, Kaytetye, Warumungu, Luritja and Arabana peoples made in central Australia in the 1900s.

The National Archives also collect and restore speech and sound. Click here to read a super-detailed history of early recordings in Australia, as well as detailed finding aids what can be accessed in their collections. Topics range from dairy production to the Navy to early broadcasting. Search the catalogue or contact them here: https://www.naa.gov.au/help-your-research

Historical New Zealand dialects

The What we hold. Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision project collects short films, newsreels, home movies and other recordings from New Zealand. The earliest recordings date from 1895…! Radio newsreels date from the 1930s and television newsreels from the 1960s to the present. Several collections hold Maori related material: https://www.ngataonga.org.nz/search-use-collection/what-we-hold/

Want to know how the NZ dialect changed from the first immigrants to the second and third generation? Listen to this fabulous, annotated example here. The National Archives collects audiovisual material. Browse it here. Their YouTube channel features films with sound dating back to the 1930s. And the National Library is in the process of digitising cassettes and LPs. On their website you can filter by city, region or decade. Their special catalogue for sound recordings can be found here.

A few very special examples, but they might be helpful: This lecture on early radio in New Zealand offers audio content samples; watch or read it here. Early NZ music recordings can be found here. How NZ politicians spoke can be witnessed in these Parliament recordings; from 1936 until today. Original voices from New Zealanders during the 2nd World War can be accessed here. Audio, video and images of a Maori World War 2 battalion can be found here.

Imitating foreign accents in English

Do you need to reproduce a foreigner’s way of speaking — for example, a someone speaking English with a heavy Indian or German accent? Then listen to these samples of foreign speakers reading English texts. You will find audio recordings from the 2000s, 2010s and today. You’ll get a detailed explanation of the entire text, both with phonetic transcriptions and details of why the accent occurs, so you can imitate it yourself. You’ll also be given tips on additional films you could watch to learn that particular accent. See an example here: https://www.dialectsarchive.com/japan-6 for a Japanese speaker. — Use their map to find the country and region you need. The site also provides a helpful list of resources for actors who need to learn an accent or dialect (some of which are no longer available, but it’s worth a look): https://www.dialectsarchive.com/links-and-resources

How to get access — faster

Three scenarios when you should email the library or archive BEFORE you spend hours searching their digital catalogues. Send an email to a sound archive…

- … when you’re pressed for time.

Browsing a database and finding things left and right might be great. It’s NOT great if you don’t have the time. If you find a sound database which might contain original audios from the time and location you’re searching — just stop.

Yes, you could spend hours searching for the right sound samples. But don’t go down the rabbit hole! We all know that your time is limited. Better to email the archivists and ask for help. They’re trained. They will find what you need in minutes.

- … if you find a data entry but no digital recording.

This means that the librarians or archivists have created a catalogue record for the file. But it’s not available for download. Or it hasn’t even been digitised yet!

The German National Library asks its visitors: »Please contact us if you find a work in our catalogue that is on a record (vinyl or shellac) but has not yet been digitised. We will then make a digitised version of the recording available to you.« The Manchester Sound Archives write on their website: »This item is an original sound. Playing the original could damage it. Please email us to request it to be digitised.« Sometimes this is a paid service, sometimes it is free. Just ask.

Mistakes to avoid when requesting digital recordings

- Be sure to request the sound files for personal use.

Mention that this is for your personal use only and that you will not share or publish the audio samples. You’re NOT inquiring to publish these materials in the film! If they get this impression, they will likely start a lengthy licensing process, and that can take a loooooong time. You’re just ordering the material for yourself to prepare for the film — make sure the archive or library understands this. Otherwise, strict copyright laws in Europe may prevent you from even getting the audios. If the audios are available but they won’t email you any MP3s, try and get your producers on board. If it’s the production company’s request, then there’s often more power behind the ask. And finally: Archives sometimes get many inquiries at the same time, so they might not understand why yours needs to be rushed. Try to respect their schedules and don’t rush them. Inquire well in advance.

Wow, this resource got larger than estimated. I hope these sources are helpful and that practising this accent is a breeze.

Have I missed a favourite?

If you know of a great sound database I haven’t mentioned, please drop me an email. And if you like what you’ve read here, I’m sure other actors will too. Share this post with your actor colleagues, dialect coaches or producers. (Or tell them in an authentic Australian or Irish accent!)

~ Barbara